The third edition of the open education project “OpenCoesione School” was launched on November 18th, 2015. While you are reading this post, about 2800 students and 200 teachers are involved in a collective learning experience focused on civic monitoring public funding through open data analysis, and also visiting sites, and conducting journalistic research.

OpenCoesione School – or ASOC, from Italian “A Scuola di OpenCoesione” – is an educational challenge and a MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) designed for students in Italian secondary schools. ASOC was launched in 2013 within the open government strategy on cohesion policy carried out by the national agencies responsible for Cohesion Policy in Italy, in partnership with the Ministry of Education and the Representation Office of the European Commission in Italy. The project is also supported by the European Commission’s network of Europe Direct Information Centres.

With a very limited budget compared to other similar practices, the project was designed in 2013 by a diverse group of experts including Damien Lanfrey and Donatella Solda from the Ministry of Education (who are now leading the ambitious Italian National Plan for Digital Schools), Simona De Luca, Carlo Amati, Aline Pennisi, Paola Casavola, Lorenzo Benussi and myself as members of the OpenCoesione scientific committee, and a specifically designated team including Chiara Ciociola and Andrea Nelson Mauro. Francesca Mazzocchi, Marco Montanari and Gianmarco Guazzo joined the team in the following editions. Other OpenCoesione staff members such as Chiara Ricci, Mara Giua and Marina De Angelis also contributed to the project.

From Open Data to Civic Engagment

The objectives of ASOC are to engage participating schools towards actively promoting the use and reuse of open data for the development of civic awareness and engagement with local communities in monitoring the effectiveness of public investment. The participating students and teachers design their research using data from the 900,000 projects hosted on the national OpenCoesione portal. On OpenCoesione, everyone can find transparent information regarding the investment on projects funded by Cohesion Policies in Italy as it provides data with detailed information regarding the amount of funding, policy objectives, locations, involved subjects and completion times. Schools can select the data they want to use in their research which can be related with their region or city.

The program is designed in six main sessions. The first four sessions aim at developing innovative and interdisciplinary skills such as digital literacies and data analysis to understand and critically understand the use of public money. Thanks to a highly interactive process, students learn basic public policy analysis techniques such as identifying policy rationales for interventions and comparing policy goals with results. This process employs “civic” monitoring tools of the civil society initiative Monithon in order to work on of real cases. Data journalism and transmedia storytelling techniques are used as well.

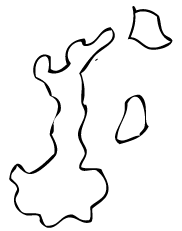

Schools that participated in the 2nd edition

During the fifth session, and based on the information acquired, ASOC students carry out on-site visits to the public works or services in their territory that are financed by EU and national funds for local development. They also conduct interviews with the key stakeholders involved in the projects’ implementation, the final beneficiaries and other actors. Finally, the sixth session is a final event where students meet with their local communities and policy-makers to discuss their findings, with the ultimate goal to keep the administrators accountable for their decisions. Here you can find all the video sessions and exercises: http://www.ascuoladiopencoesione.it/lezioni/.

Innovative learning

The teaching method combines asynchronous and synchronous learning. The asynchronous model is designed following a typical of MOOC (Massive Online Open Courses) style where participants learn through a series of activities and teachers are trained by the central ASOC team through a series of webinars. In the synchronous in-class sessions, these share a common structure where each class starts with one or more videos from the MOOC, followed by a group exercise where the participants get involved in teacher-led classroom activities. These activities are organized around the development of the research projects and reproduce a flipped classroom setting.

In between lessons, students work independently to prepare data analysis reports and original final projects. Also, in order to have an impact on local communities and institutions, the students are actively supported by local associations that contribute with specific expertise in the field of open data or on specific topics such as environmental issues, anti-mafia activities, local transportation, etc. Furthermore, the European Commission’s network of information centers “Europe Direct” (EDIC), is involved supporting the activities and disseminating the results. On ASOCs’ website there is a blog dedicated to share and disseminate the students’ activities on social networks.

ASOC’s pedagogical methodology is centered around specific goals, well-defined roles and decision-making. This has allowed students to independently manage every aspect of their project activities, from the choice of research methods to how to disseminate the results. On the other hand, the teachers are also involved in an intensive community experience that allows them to learn not only from their own students, but also from the local community and from their fellow teaching peers involved in the project.

Involving communities and policy makers

Ultimately, this takes the form of a collective civic adventure that improves the capacity to form effective social bonds and horizontal ties among the different stakeholders, actors of the local communities. In fact, detailed Open Data on specific public projects has enable new forms of analysis and storytelling focused on real cases developed in the students’ neighborhoods. This, in turn, has the key goal of involving the policymakers in a shared, participatory learning process, to improve both policy accountability and the capacity to respond to local needs.

Finally, ASOC’s key element is that the pedagogical methodology we have developed can be used as a learning pathway that can be adapted to different realities (e.g. different policy domains, from national to local, in different sectors) using different types of open data with comparable level of detail and granularity (e.g. detailed local budget data, performance data, research data, or any other type of data).

If you are interested in learning more from ASOC’s experience, you can read a case study which includes the results of the 2014-2015 edition on Ciociola, C., & Reggi, L. (2015). A Scuola di OpenCoesione: From Open Data to Civic Engagement. In J. Atenas & L. Havemann (Eds.), Open Data As Open Educational Resources: Case Studies of Emerging Practice.

Don’t hesitate to get in touch with us as we are looking forward to provide support to your institutions and communities to share what we have learned from this exciting professional journey!

Here you can watch the ASOC’s documentary video of the 2014-2015 edition https://vimeo.com/138955671

A Scuola di OpenCoesione 2014-2015: le voci dei protagonisti from OpenCoesione on Vimeo.

This is an adaptation from this post published in OpenEducation Europa. Chiara Ciociola is the main contributor, while I added a few phrases to her final version. Javiera Atenas very kindly helped us with the proof reading. I am the one who’s responsible for any inaccuracy! 🙂